Phra Ajaan Mun and the Forest Monk Tradition

Ajaan Mun Bhuridatta Mahathera

This week marks the 150th birth anniversary of Phra Ajaan Mun Bhuridatta Mahathera, a key figure in the forest monk movement that continues today to provide Thai Buddhism with valuable practices and insights.

Example of the Buddha

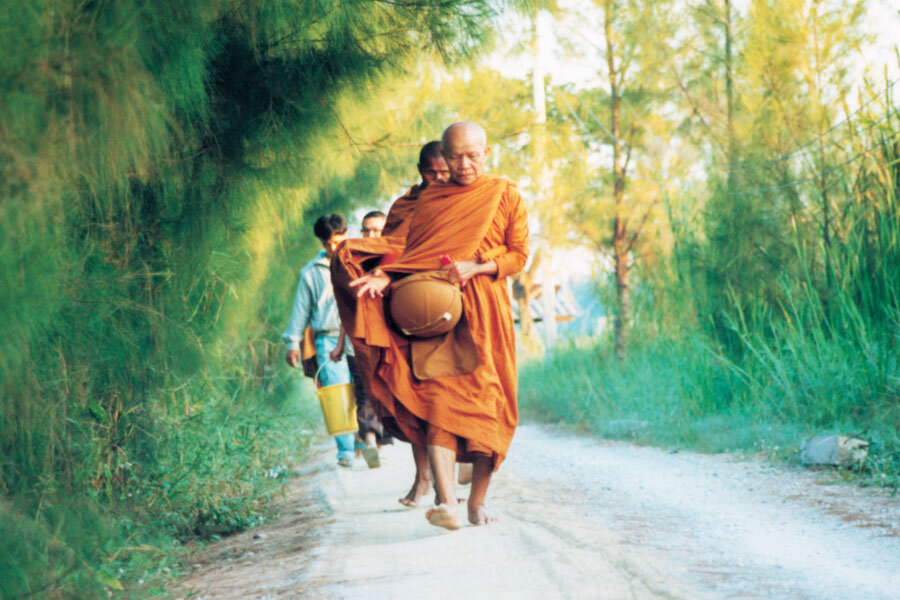

The forest monk tradition keeps alive an effort to emulate the experience of the Buddha in the forests of India more than 2,500 years ago. Forest monks note that the Buddha was born under a tree, wandered in the forest with few material possession, meditated intensively and taught what he learned from that meditation to the people he met.

Unencumbered by buildings, images, and rituals, the forest monk tradition contrasts with established urban Buddhist practices. Phra Ajaan Mun led by example, seeking out small rural wats for his rainy season retreats and spending the rest of the year as a “thudong” or wandering monk. On thudong Phra Ajaan Mun walked through the deep forests that covered much of Thailand in the early years of the 20th century.

Forest monks in our novel

Luang Paw Pat of Surat Thani

We have used Phra Ajaan Mun as one of the inspirations for Phra Som, a key figure in our historical novel “Beads on a String.” A second inspiration, also a forest monk, was Luang Paw Pat, Yuangrat’s great uncle. Like both Phra Ajaan Mun and Luang Paw Pat, the character Phra Som is caught up in the great changes taking place in the final decades of the reign of King Chulalongkorn. In parallel with the political reforms that centralized the state administration, new religious rules under the Sangkha Act of 1902 sought to centralize and standardize the practices of Thai Buddhism. The Act also provided a hierarchy of ranks based on passing examinations.

Thai reforms

In the early years of the 20th century, Buddhist practices varied widely from region to region and wat to wat. In urban wats, the Buddhist texts produced by Supreme Patriarch Wachirayaan, a half-brother of the king, set the standards for teaching the Dharma. Prince Wachirayaan was also leader of the Thammayut Nikai, a Buddhist sect that followed practices influenced by Mon monks from Burma. The Thammayut sect emphasized strict discipline and scholarly understanding of the early Pali scriptures.

In contrast, teachings at most rural wats interwove folk tales and ghost stories with Buddhist Dharma as taught through the Jataka tales, magical stories of the Buddha’s supposed reincarnations. Often un-Buddhist village traditions became part of local temple practices.

The forest monk alternative

Phra Ajaan Mun, Luang Paw Pat and other forest monks emphasized neither Pali scholarship nor village tradition. Phra Ajaan Mun specifically rejected a rank in the official hierarchy.

“I thought about it and decided that it was not a path leading to self-knowledge. If anything, honorific titles and prestige would lead to self-delusion,” he said.

Instead, he focused on meditation and learning self-awareness from experiencing the dangers of life in the forest. He followed an austere tradition that rejected material belongings and limited himself to one meal per day. He slept in caves or under the canopy of trees, with only a large umbrella, called a “klot” to protect himself from the elements.

Luang Paw Pat also spent years in the forest, but in addition to meditation, he studied herbal medicine on his travels and made curing the sick an important part of the service he provided to villagers.

Facing wild animals

Both Luang Paw Pat and Phra Ajaan Mun wandered throughout Thailand and as far as Burma and Laos. Like our character Phra Som, Phra Ajaan Mun encountered tigers and elephants in Khao Yai Forest in Nakhon Nayok province. Phra Ajaan Mun explained that he regarded all the wild animals living around him – whether dangerous or harmless – with compassion rather than with fear. He believed that all animals, like humans, must deal with their cycle of birth, aging, sickness, and death. Life in the forest, he taught, provided opportunities for reflection about one's own heart, and its relation to many natural phenomena. As Phra Ajaan Man told his disciples, until a monk actually faces these animals, he will never know how much or how little he fears them.

Battling superstition

Although Phra Ajaan Mun’s roots were in rural Buddhism, he sympathized with the Thammayut effort to root out the folk beliefs and spirit worship that was such a large part of Buddhism in the countryside. A thudong monk, he taught, must work toward spiritual liberation and that meant the fear of ghosts and spirits needed to be overcome. Similarly, Luang Paw Pat preached against superstition and emphasized the Buddha’s teaching that one should only accept what can be proved.

Phra Ajaan Mun focused his efforts in the north and northeast while Luang Paw Pat eventually established his own wat in Surat Thani province of the south. In both regions the monks found it difficult to get even their most faithful followers to relinquish long-held superstitious beliefs.

The role of forest monks today

Forest monks in southern Thailand

Today, the forest monk tradition continues to provide an alternative to both the official scholarly Buddhism and the collection of beliefs and rituals based on spirit worship and magic at many wats. The forest monk and thudong traditions offer examples of austere lives that contrast with the lives of high-ranking monks who accept cash donations and get their followers to provide them with cell phones, comfortable apartments and big cars. Forest monks remind Buddhists of the life of the Buddha, an implicit criticism of the wats that seek donations based on towering stupas, statues of Hindu gods and promises of magical powers for gaining wealth. Forest monks also perform important roles in protecting the country’s dwindling forests. Living in those forests means they are often out of sight of increasingly urbanized Thais, but they should not be forgotten.